This fine rendition of William Atkin's Fore An' Aft

design, shown without the topmast rigged, was built by Russell Dyer. The

lower photo gives a hint of her lines and indicates great promise of easy motion,

good course-keeping ability, and speed in a wide range of conditions.

This fine rendition of William Atkin's Fore An' Aft

design, shown without the topmast rigged, was built by Russell Dyer. The

lower photo gives a hint of her lines and indicates great promise of easy motion,

good course-keeping ability, and speed in a wide range of conditions.WHEN WE bought Eric, our 32' Atkin ketch, the man who sold her wept openly while he signed the papers under the kerosene lights of her saloon. For us it was a deliriously happy day, but I knew exactly how he felt. Many times since then I have reflected on the depth of the relationships that he and I have had with this small and humble old boat, and I think of how she has similarly enriched all her owners' lives. We'll go on to discuss several aspects of the Atkin design legacy, but no other point is more important. This deep and rewarding relationship with a boat is just what the Atkins felt, and is exactly what they intended for us to feel about their designs. All boats have personalities -- good, bad, bland, obnoxious, noble, humble, proud, faithful, or treacherous. The Atkins knew this. Almost every one of over 800 designs was referred to by a different name, chosen by the designers as the boat was being drawn, and they wrote with sincere emotion about all of the designs that saw print.

It seems to me that there are two major creative impulses that dominate the field of yacht design: the ideal of Efficiency, and the ideal of Romance. If a design is devoid of either quality, it is not as good as it could have been. If the design is poorly conceived in a technical sense, all the traditional gear and atmospherics in the world will only serve to clarify the fact that she is a tub. If a boat is created only as a machine, it will be cold, lifeless, and uninspiring -- whatever it's other virtues. It was always important to the Atkins that their designs be technically "right," but they also wanted the boats to be loved. Even their workboats, military craft, and "modernist" boats had at least a taste of romance.

Students of the Atkin designs should not make the mistake of looking at some of the more well known boats and dismissing them as "character boats" because of the gaff rigs, bowsprits, bulwarks, and what we now call "traditional" character. Many of the boats were designed a long time ago, in a small but lively marine culture still connected to its past, when such features were modern and traditional at the same time. It is better to ask why these designs have continued to have appeal to this day, and why William and John were frequently called upon to produce variations on those same designs years later. The answer might be that the boats were technically excellent to begin with and also had a romantic appeal that never became outdated -- a good enough definition of enduring quality in design. It should be pointed out that none of the designs is purely romantic. Such boats would quickly become tiresome in real-world use. On the contrary, the most romantic looking of their designs serve to educate us as to the real-life utility of older style gear and features, properly executed.

THE ATKINS are most famous for their handsome, heavy displacement double- enders, but this is probably just because these boats have been the most interesting to the most people for the longest time. Between them, in careers spanning over 80 years, William and John produced 873 designs -- an almost unmatched number for a firm which seldom employed draftsmen. Their output included offshore and inshore cruising sailboats, racing and cruising powerboats, rumrunners, luxury motor yachts, racing class sailboats, Sea Bright skiffs, rowing and sailing skiffs, outboard boats, dories, military craft, houseboats, and even a "Powered Snow Yacht". So, how would we characterize them?

First and foremost, the designs are competent. Both Atkins were hands-on types. William started out running a productive boatbuilding yard. Both he and John built boats from the time they were very young, continuing to do so off and on throughout their lives. There was evolution in their thinking about construction over the years, but they always had the builder in mind and understood when to employ complex structures and when to keep things simple. Unlike many designers they seldom if ever drew anything that couldn't be built as drawn. The Atkins were always interested in new materials and methods; and, with their lifelong involvement with marine publishing, they had constant exposure to other people's ideas. Their work evolved as a result, but they had to believe in a new feature before they employed it.

The Atkins owned and used boats, beginning with William's first cruise in 1904 aboard an open power launch, and continuing through a series of modest sail and power boats to the pulling boat George, which John enjoyed in his retirement. At one point William owned the sloop Great Republic, made famous by Captain Howard Blackburn's singlehanded transatlantic voyage. Later he designed and built the well-known Ben Bow for his own use. John and his wife Pat cruised for many years in We're Here, a small motorsailer he designed and built. The Atkins were not academics -- they understood the actual real-life impact of every line and specification.

Vega is a big, tough,

simple boat which makes most

modern center-cockpit types look positively wimpy. Her no-nonsense interior has a

whole lot of room, including in the after cabin, which is by no means the usual

afterthought. Her half acre of deck space would be a boon to the liveaboard.

Vega is a big, tough,

simple boat which makes most

modern center-cockpit types look positively wimpy. Her no-nonsense interior has a

whole lot of room, including in the after cabin, which is by no means the usual

afterthought. Her half acre of deck space would be a boon to the liveaboard.

An Atkin boat always has at least a taste of salt to her, whether it be a strong and vibrant theme as in their many ocean-going cutters, ketches, and schooners with their universal air of confidence, ability, strength, and dependability. Or it might be in something that catches the eye in a humble sailing surfboard. In this quality of salt one senses that a vessel is not just on the sea, but of it

I perceive a style in the Atkins' work -- not a consistent style, but individualized quirks and nuances put into each design. This might exist only in the shapes of the hull itself, which in a few cases are as much artistic as practical, or in a sassy and unexpected window shape in a fast motor boat -- or it could be just a certain combination of sheer, ends, cabin trunk, and ports. It is identifiable in most of the boats, and it is what ultimately defines their personality.

The Atkins designed a few very large yachts, but their primary interest was in boats which were within the reach of average people. William and John clearly liked to think of themselves as average people, and their writing reveals an almost total boredom with wealth or status. This concern for average people is not always immediately apparent to us nowadays, as we have come to associate the idea of inexpensive or home-built boats with boxy plywood craft. The Atkins never thought conventional types of wooden boatbuilding to be beyond the ability of the amateur. Some of their designs were made quite simple, for easy construction, and some were not, but the assumption seems to have been that any builder's primary goal would be to build a good boat -- and it was not supposed to be a cause of suffering! It would seem that they understood the real cost of a boat is not determined on the day she is launched, but on the day she is sold. A boat that is beautiful, inspiring, rugged, and long-lived may well bring more dollars when she is sold than she cost to build A different sort of boat might bring next to nothing

Measuring only 18' on deck, Retreat

is the smallest of a number of charming Atkin houseboats. While few would choose

to carry their minimalism this far, perhaps she will provide some assurance that

there is a good life to be had on the water, no matter how tough times might get.

Measuring only 18' on deck, Retreat

is the smallest of a number of charming Atkin houseboats. While few would choose

to carry their minimalism this far, perhaps she will provide some assurance that

there is a good life to be had on the water, no matter how tough times might get.WILLIAM ATKIN began his career in 1906, at age 24, in Huntington, Long Island -- a time when Huntington was rural, pretty, and unspoiled. In August of that year, he and his 19 year-old friend Cottrell Wheeler acquired a 30' x 50' boatbuilding shop which had formerly belonged to Charles G. Sammis, and which they always referred to as The Red Boat Shop. It is unclear what the arrangements were, but Sammis and his son Percy continued to work for the firm of Atkin & Wheeler.

There then followed a period of intense activity and equally intense enjoyment, during which friendships which would last Atkin the rest of his life were firmly cemented. Atkin said of this time, "Cottrell Wheeler and I found ourselves in the business of building small custom built motor boats; 'launches' these were likely to be called in those far-away free days. The boat shop was at the creek-side at the head of the harbor at Huntington, ...and a grand place it then was. The air fragrant, and the harbor and creek water so clean we fished for smelt and mackerel from the boat shop windows, while landlubber Isaac Waltons cast their flies for brook trout less than a half a mile upstream. Huntington Harbor was a delightful place in those good days.

"It is doubtful whether any two young men embarking on life's uncertain path ever had as much fun while working as we. Building boats for individuals took on the aspects of a pastime rather than an occupation. This was a happy way to begin what has turned out to be a long vocation...

Atkin & Wheeler got its start in Huntington

Long Island, when the two young men bought the yard of Charles G. Sammis.

Thereafter it was always referred to as The Red Boat Shop, and it was the scene

of remarkable productivity and valued friendships to which William Atkin would

frequently refer throughout his career.

Atkin & Wheeler got its start in Huntington

Long Island, when the two young men bought the yard of Charles G. Sammis.

Thereafter it was always referred to as The Red Boat Shop, and it was the scene

of remarkable productivity and valued friendships to which William Atkin would

frequently refer throughout his career."We had friends, Cottrell and I; among these George A. Fairfield of Minneola, New York, and Roswell Davis of Middletown, Connecticut. The former M.I.T., 1903 or thereabouts, a civil engineer; the latter M.I.T. about a year later, with a degree to practice naval architecture. You might say these two were friends of the shop and that the place had a community of interest for the four of us not ever likely to be repeated this side the rolling Jordan, and certainly not among the ownership and clientele of our modern quantity-production boat shops.

"I am afraid we were not very efficient -- but we had grand times; the boats came a-pace and we were very happy..."

He would frequently return to Huntington days in his writing over the years, recalling his own youth, that of Huntington, and the younger days of yachting. It's difficult to write about the personality of someone whom one has never met, but one thing is clear. William Atkin was the kind of man people liked, and who valued friendship. Fame never changed this. His writing addressed many aspects of the world of boats over the years, but woven throughout was a belief in simple pleasures, and chief among these was friendship.

At first glance, a miniature schooner built to the

Coot design might seem to be something of a toy; but one of the

boats, the 27'2" Nakomis, has debunked that idea, with many

successful high-latitude and transoceanic voyages to her credit.

At first glance, a miniature schooner built to the

Coot design might seem to be something of a toy; but one of the

boats, the 27'2" Nakomis, has debunked that idea, with many

successful high-latitude and transoceanic voyages to her credit.ATKIN & WHEELER was ideally situated both geographically and historically, for they designed and built about 19 boats in this shop. The first was Rosetta V, a 40' bridge-deck power cruiser for Dr. Ferdinand Valentine, a specialist in "the diseases of wayward men." Reminiscences about the time mention long hours and hard work, but not the economic problems that plague many new boatbuilding shops. Their proximity to New York must have placed them in a lively economy, and despite their youth and a lack of credentials, they attracted a great deal of business. It is notable that they were apparently building only boats which Atkin designed -- an even greater leap of faith on the part of their customers, and it can only be explained by the fact that even the earliest designs must have been good.

For the most part, the early boats were power driven, apparently to satisfy an intense demand for boats of that type. The marine press, for the next couple of decades, seems to have been preoccupied with power boats much as was Atkin & Wheeler. It seems likely that many people were of the belief that power would largely replace sail. It probably took a while for everyone to realize that while some would immediately choose the speed and luxury of power when it became available. Others would find plenty of reason to stick with sail-powered yachts.

Here is the 18' Gretchen,

an inshore tabloid cruiser

with very shoal draft and some Dutch styling overtones. The raised deck provides

sitting headroom that can be used in lean-back comfort. The leeboards allow shoal

draft (17") without the complication and interior obstruction of a centerboard

trunk.

Here is the 18' Gretchen,

an inshore tabloid cruiser

with very shoal draft and some Dutch styling overtones. The raised deck provides

sitting headroom that can be used in lean-back comfort. The leeboards allow shoal

draft (17") without the complication and interior obstruction of a centerboard

trunk.Sailboat design in general went through some changes, too, first in order to accommodate auxiliary engines, and then to cope with the implications of them. Many cruising sailboat designs from the early part of the century have been roundly criticized for lack of windward ability (and a few Atkin designs are of this type), but it appears that for a while many people believed that no one who could power to windward, would choose to sail. And there is a certain logic to that, although ultimately cruising sailboats as a rule retained windward ability, and in fact later on became obsessed with it. In my opinion, the average contemporary cruising boat is entirely designed around windward ability, and sometimes sacrifices a great deal to that end. Of course she is also typically powered to windward -- just one of the absurdities of our modern age.

At first Atkin seems to have been interested primarily in high speed power boats, but after a few years his interest switched to cruising boats of both power and sail. It might be that successfully competing in increasingly high-tech racing powerboat design quickly became too expensive for a small shop to handle, or it might be that the appeal of other types of boats was just too strong to resist.

The Red Boat Shop provided a good starting point, but it had been constructed for earlier boatbuilders who used no power tools. Atkin & Wheeler wanted to take advantage of technological advances which had come along, and stationary power tools of the day took up considerable floor space. So in 1912 they designed and built The New Shop, a 50' x 80' building with two floors and a basement, a machine shop, an improved dock, a 10-ton crane, and a railway that had water at any stage of the tide, thanks to a dredged channel. The new building, designed by Atkin, suspended the second floor from the roof structure to allow plenty of unobstructed space on the first floor -- a feature considered radical by local critics, but which proved to be successful. Here they built 31 boats, ranging from an 18' hydroplane to the 115' express cruiser Cabrilla. It seems there was nothing that Atkin & Wheeler didn't dare to tackle, for they not only designed and built Cabrilla herself, but her twin 750-hp V8 engines and transmissions as well, not something the average local boat shop would expect to do today!

Morning Star, a gaff-rigged sloop, was built to William Atkin's

Dolly Varden design. Both

Atkins' small cruising boats very seriously. Scores of such designs explored almost

every possible variation, and all share the sense of authenticity and charm

displayed in this example.

Morning Star, a gaff-rigged sloop, was built to William Atkin's

Dolly Varden design. Both

Atkins' small cruising boats very seriously. Scores of such designs explored almost

every possible variation, and all share the sense of authenticity and charm

displayed in this example.Charles and Percy Sammis continued to work for Atkin & Wheeler, along with an enlarged crew, and production grew to match the capacity of the new business. But it was a move that tripled their overhead, and Atkin would ultimately regret it. Under the heading, "This Business of Growing Larger," he wrote: "And, to make a worse picture of it all, the workmanship and materials of the little Red Shop were equal, if not superior, to that produced by the new one. Over a very long period of time my experience has been, and is, that the small boat-building establishment in which the 'boss' works with two or three hired hands is by every measure of value a far better place to patronize than any shop of pretentious character; and, furthermore, that these small shops are able to build boats of superior design and of better quality for less money than not only the larger custom builders, but the 'rush-'em-through' builders of the so-called 'stock cruisers' as well." Sentiments with which the author wholeheartedly agrees.

IN THE same year that the New Shop was built, Atkin allowed himself to be convinced to write an article for The Rudder magazine on the technical aspects of the high speed powerboats gathered in Huntington for the Harmsworth trophy races. It was the beginning of a lifelong involvement with marine writing, and while he was always a naval architect first, he was a marine writer second, to a greater degree than any other designer of his time.

The 115' motoryacht Cabrilla, designed

by William Atkin and built by Atkin & Wheeler, represented quite an

accomplishment for a small yard and young designer.

The 115' motoryacht Cabrilla, designed

by William Atkin and built by Atkin & Wheeler, represented quite an

accomplishment for a small yard and young designer.Boats seem to inspire more writing and analysis than almost any other field of interest, and the use of boats and what is written about them seem to be so tangled up together that it is difficult to say whether, for many people, boat ownership is primarily a physical or an intellectual activity. Perhaps such an intermingling of science, fantasy, and nature is what is meant by "romance." However that may be, Atkin obviously loved to write about all aspects of boats, especially the romantic appreciation of the boats themselves, and the people and places with which they were associated. Those accustomed to strictly analytical writing may at first be baffled by apparent contradictions in William Atkin's writing. He seems to say that first one type of boat or boat detail is better, then another. The fact is that he loved many different types of boats, for different purposes -- a perspective which will seem logical to any non-specialized naval architect, but which may be confusing to the newcomer to boats who is looking for "the right answer." The net effect of Atkin's writing is to broaden one's interest, deepen one's appreciation of the right boat for the right job, and heighten one's enjoyment of sincerity and good character wherever it is found. William Atkin always addressed his reader as "Shipmate" -- a personal, human perspective, not a lofty scientific one. Without the writing, William Atkin would still have been one of the most popular yacht designers of his time. With the writing, he was the most beloved.

The firm of Atkin & Wheeler lasted until the first world war, but ceased operations at that time, for reasons unknown. All Atkin says about it is, "Our work had been the designing and building of pleasure craft, for which wars allow no time or energy." Presumably there was war-time boatbuilding to be done, but it may be that the transition simply came too soon after their commitment to the larger shop for them to survive -- not the first or last time that politics would heavily impact small boatbuilding shops.

During the war, William Atkin served as editor of Yachting magazine -- quite an achievement for a young boatbuilder with little publishing experience, and it was something which he evidently enjoyed, for there then followed a period of intense involvement with marine publishing. After three years at Yachting he joined the staff of MotorBoat (not to be confused with Motor Boating) as technical editor, beginning a happy association with Editor William Nutting, for whom he designed the well known ketch Typhoon, in 1920.

Typhoon measured 45' on deck. She was apparently intended to demonstrate Atkin's and Nutting's concepts for a faster boat than others of her size, as her proportions are radically different than typical boats of her day. She was extremely fine forward, and indeed could almost be said to be "all entrance" clear back to amidships. She had a very straight run and an unusually broad transom, thus completely breaking with any traditional notion of "balance" between the forward and after shapes of the hull.

On her maiden voyage, she made an extremely fast transatlantic passage from Baddeck, Nova Scotia to Cowes, England. She covered the 2,777 nautical miles in 22 days, 1 hour, and 22 minutes, in a headlong rush before strong fair winds -- the weather being due as much credit for the speed of the passage as the design, perhaps. Typhoon received much attention in the marine press, but Atkin didn't continue to work with the hull type. Virtually all of his subsequent designs retained a "balanced" hull form in which the after body was not much fuller than the forebody, as is commonly said to be desirable for good motion and handling in storm conditions, but it is never said that Typhoon was deficient in these respects.

In 1920 William Atkin designed Typhoon

for William Nutting, editor of MotorBoat magazine. Nutting sailed the 45'

ketch transatlantic, from Nova Scotia to England, in little more than 22 days.

In 1920 William Atkin designed Typhoon

for William Nutting, editor of MotorBoat magazine. Nutting sailed the 45'

ketch transatlantic, from Nova Scotia to England, in little more than 22 days.During the MotorBoat period, Atkin continued to work independently at his design work, and examples appeared not just in MotorBoat, but in the other major magazines as well. Among other types, he had made a considerable study of the Sea Bright rowing and power skiffs of the New Jersey shore, for which he had great admiration. He and John would continue to design variations on this very useful type for the rest of their careers.

The Sea Bright type evolved for use by the local fishermen. There being few harbors, it was necessary for the boats to be launched off the beach and to return to the beach, every day. While they were round-bilged boats, instead of a conventional centerline structure they had a narrow flat bottom like a dory. The boats always had broad transoms, but the bottom came to a point at both ends, forming a hollow skeg or "box garboard", aft. They would thus remain upright on the sand, and could be dragged around or moved on rollers with ease, and with little wear and tear.

By coincidence, the basic form was well suited to inboard power, and when gasoline engines appeared the Sea Brights quickly adopted them, with little modification to the basic boat except a subsequent gradual increase in size. The flat bottom made it easy to install the engine, and when the box garboard was made slightly deeper, it's after end made an ideal place for the shaft to exit the hull. Using a two bladed prop, the boats retained their beachability -- all that was necessary was to remember to turn the propeller blades sidewise before hitting the beach.

Ultimately the Atkins were to design just about every conceivable variation on the type, from historically correct beach boats to large sailing and power yachts which in no way resemble the originals except in the configurations of their hull structure. One of the most important variations appeared first in the form of Mischief, published in 1921. She was the first Sea Bright to incorporate hard chines, and straight bottom sections which, in their progression from forward to aft, warped from a truncated "V" shape forward to an "A" shape aft, creating a recessed, protected area for the propeller, and a very shallow draft hull that offered good speed. William and John were to design many boats of this type over the years, and it remains one of the best ways to create a healthy, ultra-shoal-draft powerboat.

![]()

John Atkin did a lot of surveying. With his lifelong

exposure to yacht design, construction, and cruising, he was uniquely qualified for

this vocation. His surveying work helped him to design structures that were

strong and resistant to deterioration.

John Atkin did a lot of surveying. With his lifelong

exposure to yacht design, construction, and cruising, he was uniquely qualified for

this vocation. His surveying work helped him to design structures that were

strong and resistant to deterioration.A SERIES of events, which began in 1923, was to have a major impact on Atkin himself, and his career. Discussions with Nutting led to a design concept for Eric, a 32' double-ender based on the 47' Colin Archer designed Redningskoite, a Norwegian sailing rescue craft. She was to become Atkin's single most popular cruising boat design (see related story). Unfortunately, Nutting chose not to have Atkin finish the design, and instead purchased Leiv Eiriksson, an existing Norwegian boat of similar overall type, but which may have been different in many important details. In any event, the vessel was lost without a trace along with Nutting and his crew, on the way home from Norway.

The impact on Atkin must have been considerable, and the event is mentioned often in subsequent writing, but never in a tragic light. In print, he romanticized his friends' deaths, weaving them into a bittersweet, poetic, and mystical portrait of the sea. Among other things he did a portrait of Leiv Eiriksson in silhouette, showing her clearly identifiable crew, afloat and alive. He wrote, "One of these autumn days, Leiv Eiriksson will come in with the northeast wind behind her; she will come up the Sound, and the air will be crisp by then. I sometimes think it might be well for those who keep their boats in late to save a full four fingers of something that is strong, and drink this down standing (if there is headroom) to appease the anger of the Gods. They may not fancy the temerity of anyone who attempts to retrace the sea path of an ancient Viking -- no not even though he be a thousand years behind. On after thought, a tumblerful might be much better...

"For God, and the rest of us, now know that it is no light task to traverse the seas of the North... Old Neptune and his handmaidens splashing about in Davis Strait must have remarked upon [this] modern white-hulled Norse craft splashing through his sea. How long a time, he must have mused, had bandled by since the Dragon and the Long Serpent pressed on to make the land? Aye, a full thousand years for sure!

"Perhaps he smiled -- or swore.

"At any rate his handmaidens hit their stride; and somewhere there in the Northern sea the Leiv Eiriksson lies silently, while her crew sleeps on forever.

"And it is all too bad. Children, widows left; and an epic of ocean cruising unwritten! But that, reader, is the way of the sea."

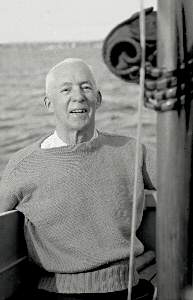

William Atkin in later years. Both Atkins enjoyed a deep and warm

affection for good people and good boats. William's special talent was evoking those feelings in a form that people of modest means could make their own.

William Atkin in later years. Both Atkins enjoyed a deep and warm

affection for good people and good boats. William's special talent was evoking those feelings in a form that people of modest means could make their own.There are no visible changes in the nature of Atkin's work which can be specifically attributed to the loss of Leiv Eiriksson, but it is notable that the design for Eric was finished up anyway, and her design went on to become famous as a tough and dependable offshore voyager. Indeed, while both Atkins' work was too broad to be narrowly categorized, they have always been best known for their staunch and reliable offshore cruising sailboats, which while they were no more immune to the consequences of human error than any other boat, were as unlikely to perish by the forces of the sea as any ever designed. Still it seems as though a part of William Atkin was always waiting for Leiv Eiriksson to make port, and even when he doesn't refer to her directly, she seems to remain in the background of much of his poetic writing:

"I address this to one of my Shipmates;

"An incessant song has been with me this last year. Every leaf sings it; and the tide as it runs down the channel.

"As I love the sea; so I love the land. I know where the wood violets grow as well as where the eddies flow.

"Quite true, Shipmate.

"One wanders through a Paradise when recollections come drifting by; one gathers fragrancies from these. Why yes, Shipmate, it is all like some magic book. We come thus far, and suddenly the covers close! Thenceforth we conjecture for the morrows.

"It is like looking straight down a narrow lane of trees, on either hand foliage, and the same overhead, but at the far end there is an arched opening showing grain bowing before the south wind, which appears very much like the sea. We know quite well what we have passed through; but are not so sure of the voyage ahead.

"Somehow as we cruise around we become more and more confident; difficulties confront us, adverse winds, bad tides, yet never do we consider foundering. And this is well and good. And we are not afraid to look beyond the bowing grain or the crest of some tremendous sea...

"And thus it is that we look confidently into the days beyond the horizon. We are... quite unafraid of the voyage before us. For the tides may ebb and flood, and the winds may come and go, and just the same shall we sail through a Paradise of recollections and of faith in days to come, with the fragrancies of all the seas for company.

"Quite true, Shipmate."

IN THE spring of 1925, three sister ships built to the Eric design were launched, and named Freya, Valgerda, and Eric. Of them, Atkin wrote as they were building:

"It is a long, long voyage from Lyngor, on the south coast of Norway, to Huntington Harbor. But if you will walk across the Mill Dam Road at the head of Huntington Harbor in the half light of the evening you will have a momentary thrill which will carry your fancies abroad; for, just as sure as anything, there looms the silhouette of a skoite, in frame, with two others nearby.

Pat and John Atkin cruised Long Island Sound in

We're Here, an economical displacement-hull motorboat with sails.

At the time of this photo, she belonged to Mike and Shirley Dagostino and had

been renamed Shirley Mae.

Pat and John Atkin cruised Long Island Sound in

We're Here, an economical displacement-hull motorboat with sails.

At the time of this photo, she belonged to Mike and Shirley Dagostino and had

been renamed Shirley Mae."About this time the lights of a passing motor car will disclose the terrain as being quite a part of Long Island. What in the dusk seem to be bold rocks, with lagoons between, prove to be thatch bog, showing bare when the tide is at half ebb; what sounds like water lapping on the stones is the overflow from the mill pond pouring through the flume; [but] what seems to be a skoite in frame, with two others nearby, is a skoite, and the other two, her sisters."

Clearly he felt some of what we now call "closure," in the realization of the boat which he and Nutting had planned, and which he must have fervently wished that Nutting had built instead of making his date with destiny.

The yard which built the three Erics was that of Richard B. Chute. With that project it became Chute & Bixby. Mr. Bixby was apparently a businessman who financed the three boats, which were built on speculation, with two of them being sold while under construction. Chute & Bixby went on to build a great many Atkin boats through the years.

After the loss of Nutting, MotorBoat magazine lost its appeal to Atkin. He ceased working there and began the series of articles and designs for Motor Boating, edited by Charles F. Chapman, which continued for many years and were reprinted in the Motor Boating Ideal Series, a collection of designs and articles in book form, in over 40 volumes. It is at this point that the amazing pace and productivity of Atkin's work habits become most obvious, because throughout this time period, he produced a complete design with commentary for every issue of Motor Boating, while at the same time he drew commissioned designs for other customers, all without assistance until his son John joined him at the work, after World War II. He did most of the work at night, and offers us this picture of his routine: "Somehow I cannot get started on any sort of work early in the day. When the sun first comes I sleep in peace and let the early world go by. And then when the sun finally gets up steam and warmth I always have to sit around and worship its fragrancies; and then, like enough, I acquire an urge that cannot be easily set aside, to go and look out across the Sound. By this time it is noon. There will be a raft of letters heaped on the pile that has been collecting on my desk for the last week, and I am constrained to reply to these. By sunset, I sharpen pencils, pin down a clean sheet of paper and draw, and draw, and draw."

Probably no other designers have lavished as much

attention on flat-bottomed skiff as the Atkins.

Willy Winship

measures 13' 9" in length and carries 92 sq ft of sail.

Probably no other designers have lavished as much

attention on flat-bottomed skiff as the Atkins.

Willy Winship

measures 13' 9" in length and carries 92 sq ft of sail.WILLIAM ATKIN began his own magazine in 1926. Fore An' Aft (subtitled "A cruising magazine conceived by cruising men and dedicated to cruising.") was a sincere and appealing journal devoted to cruising in small yachts -- it covered boats of no more than 50' in length. The publisher was Henry Bixby, of Chute & Bixby. Most issues contained Atkin designs and articles, along with those of other designers and articles by cruising people. It shared a feature with some other magazines of the day, in that every issue had the same cover -- something no circulation manager or designer would allow, nowadays! It also did not sell advertising in the usual way. No one was allowed to advertise whose products Atkin did not feel he could personally recommend -- a degree of idealism not seen since. An interesting service was the "Shopping Department." The idea was that anyone desiring to purchase anything relating to boats could contact the magazine, which would determine what was the best item of that sort available, providing it to the reader at a reasonable cost, while retaining a markup. The magazine was thus a sort of universal catalog. Typical of the honest charm of Fore An' Aft was the "Shopping Department Ad," a full page containing only the following words: "The Shopping Department. If you want anything, let us know."

It was a fine magazine, a handsome magazine, aimed at a narrow audience, and with few advertisers -- not the usual formula for success, but it went forward in apparent good health until the spring of 1929, when it skipped a few issues, reappeared under different ownership and with no trace of William Atkin, and then ceased to exist. It is possible that like so many magazines it simply failed due to an insufficiency of advertising and other income and high expenses, or it may be that once again the course of national events simply overwhelmed it, along with so much else.

John Atkin's popular

Little Maid of Kent

design describes a schooner of just 30' in length. This example was owned by

Irving Giese, and was photographed in Ascona, Switzerland.

John Atkin's popular

Little Maid of Kent

design describes a schooner of just 30' in length. This example was owned by

Irving Giese, and was photographed in Ascona, Switzerland.Another attempt at a regular publication came in 1947, with the first volume of The Book of Boats, which was to be a quarterly publication, in book format. Two volumes were printed, and publication then ceased, but they were subsequently reprinted. In the introduction was this characteristic statement by William Atkin: "Perhaps in the bewilderments of a modern world where almost everything is highly appraised because of its huge size, its gaudy expanse of chromium plate, its marvelous complication, its industrial streamlining, its tremendous popularity, and the noisy ballyhooing accompanying it all, the wholesome, plain and genuine character of The Book of Boats series will fill a place in the cabin book shelves which has many years been empty." Atkin had obviously now found that his work was contrasting with what I would call "modernist" trends in design. The Atkins occasionally indulged in "modern" flights of fancy, such as one speedboat which very strongly resembles a '57 T-Bird, but in general it would seem that they saw their work as a logical continuation of unbroken evolution and refinement of concepts defined not by stylists, but by the sea itself, the constant around which they worked.

Designed by William Atkin and built in

Darien, Connecticut, after the 1938 hurricane destroyed the Atkin home and

office on Pratt's Island, Anchordown combined nautical and light art-deco themes.

It still stands, as a private residence in a prosperous suburb.

Designed by William Atkin and built in

Darien, Connecticut, after the 1938 hurricane destroyed the Atkin home and

office on Pratt's Island, Anchordown combined nautical and light art-deco themes.

It still stands, as a private residence in a prosperous suburb.DESIGNS AND articles came in a steady stream through the Great Depression, and there can be no doubt that Atkin's sincere devotion to small boats and economical yachting, combined with his romantic and lyric descriptions of the simple pleasures of life with the water, must have endeared him to thousands of readers, for whom he made such happinesses possible, or at least imaginable, helping to relieve the heavy burdens of hard times. John Atkin began to assist his father around this time, and his first published design, the dory Active, appeared in The Rudder magazine in 1937.

The 1938 hurricane, arriving as it did without warning, hit the Atkin household very hard. Their home on the eastern tip of Pratt's Island on Long Island Sound was utterly destroyed, along with the design office and many plans, and William and Dorcas Atkin and their sons William, Jr., and John had to swim for their lives at the height of the storm. These events are described with characteristic avoidance of the tragic aspects of the calamity, but much that was of value to the family and to posterity was lost. Fortunately most of the original plans were stored at William's mother's house in New Jersey. A new office named Anchordown was soon built in Noroton, Connecticut, to plans by Atkin which combined nautical elements with contemporary ideas of modernity, in an appealing design with a flat roof, glass block windows, a blue neon light over the front door, round- cornered doors, etc. Originally built in a rural area, the building, which still exists, is now surrounded by a sophisticated Connecticut suburb.

If there is a simple boat that can offer the

Herreshoff 12 1/2 some competition for the title of best small keel daysailer,

Teach might be it.

Her large stern deck gives a secure feeling and

helps to ensure that crew weight will be kept amidships where it belongs in

such a small boat, and there is a lot of useful space for seating a small crowd

or cruising with a boom tent. Her double-ended character is something out of

the ordinary, and combined with the long keel, ample ballast, and easily

handled rig, she will be a reliable and reassuring boat to sail.

If there is a simple boat that can offer the

Herreshoff 12 1/2 some competition for the title of best small keel daysailer,

Teach might be it.

Her large stern deck gives a secure feeling and

helps to ensure that crew weight will be kept amidships where it belongs in

such a small boat, and there is a lot of useful space for seating a small crowd

or cruising with a boom tent. Her double-ended character is something out of

the ordinary, and combined with the long keel, ample ballast, and easily

handled rig, she will be a reliable and reassuring boat to sail.NO ONE has done more to romanticize yachting in an appropriate way than William Atkin, but that romanticism did not extend to war. The design named Jerry Colemore got its name from a young man from England who was a close friend of the Atkin family. On the outbreak of the second world war, his parents insisted that he do the honorable thing, and he returned to England to join the RAF, leaving behind his American friends and an old Friendship sloop named the Irving D. Olson. To the Atkin family's great grief, he was promptly killed in action. In his article on the boat named for his young friend, Atkin indicates that he felt that an indolent life on the Olson might have been better than an honorable death at the age of 19.

In the years preceding his own direct involvement in the war, John Atkin worked as a draftsman first at the Consolidated Shipyard, and then at the Luders yard, where he worked for more than four years. Eventually he served in the Pacific as a civilian, on an oceangoing tug. At the Atkin office, William's war years were largely occupied in designing tugs, patrol boats, and the like, along with a steady stream of yachts. For once, the firm employed draftsmen, with Nils Olhman, Danny Potter, and Bob Hamilton serving in that capacity. There is a design for a 7'6" sailing pram done by John during his free time, and planned around materials available aboard his ship, upon whose deck it was built. It is named Saipan, after the place John was writing from at the end of the war, with a wonderful description of the celebration of victory among the fleet. In William Atkin's published presentation of the design, one can sense the intense relief which was flooding the whole world at the time.

Ninigret (22' LOA) is one of John

Atkin's most popular bass boats. Her cuddy features a removable canvas top, and

offers comfortable seating away from the fishing action, a couple of berths when

wanted, and the option of a more-or-less private head.

Ninigret (22' LOA) is one of John

Atkin's most popular bass boats. Her cuddy features a removable canvas top, and

offers comfortable seating away from the fishing action, a couple of berths when

wanted, and the option of a more-or-less private head.John Atkin joined the design office after the war, and brought with him an infusion of youthful vigor, new ideas, superb drafting skills, and an artistic talent which if anything, exceeded that of his father. With both of them working, they had planned to reduce the number of days they worked, after the war, so as to spend more time relaxing on the water. Unfortunately the inflation and high taxes of the postwar period made this impossible, and work continued at a fast pace.

It is interesting to compare the work of the two men. John's lettering shows a firmer hand and more style than William's, and his drafting is more precise. It reproduces better, due to more careful attention to the weights of the lines. John's designs tend to have springier sheers and more careful attention to "style" beyond function and convention. But there was little attempt to keep their work separate, and it is impossible to say with absolute accuracy who did what. Some designs appear to be John's concepts with drawings and some details done by William, and some the other way around. Some designs were published under William's name that appear to have been drawn by John, and the author is of the opinion that at least a couple of descriptions were written by John in William's style, and published as William's. But it was clearly a close cooperation, so these things are to be expected, as frustrating as they might be to historians. Naturally William was beginning to slow down, after hundreds of designs and decades of extraordinary productivity, and gradually his volume of work receded and John's became predominant. William Atkin died in August of 1962 .

William Atkin always toyed with the idea of

moving to Maine. This Banks dory named Pemaquid

is one of design

that he drew with the Maine coast in mind. She has about as much sail as an

unmodified dory form needs or can carry, and she also has a small inboard

engine and some outside ballast. This is a simple boat with a lot of room and

real rough-water ability. It might be nice to add some flotation, as she is

all open.

William Atkin always toyed with the idea of

moving to Maine. This Banks dory named Pemaquid

is one of design

that he drew with the Maine coast in mind. She has about as much sail as an

unmodified dory form needs or can carry, and she also has a small inboard

engine and some outside ballast. This is a simple boat with a lot of room and

real rough-water ability. It might be nice to add some flotation, as she is

all open.IN MY opinion, John Atkin was if anything a better designer than his father, and it would certainly please William that it be so. William is perhaps more famous, but this is probably because he was nearly as much of a writer as he was a designer, so his work always benefited from a thorough description on both a technical and an emotional level, making it easy for an unusually wide range of readers to understand it and feel the love he put into it. William worked at incredible speed, and while his boatbuilding experience prevented him from drawing things which couldn't be built (a common problem among designers) occasionally some of the details and concepts were not as good as the others were. It is evident that John took a great deal more time with each design -- every drawing is a work of art, and every line of every boat seems to have been drawn with the greatest of care. Absorbing William's romanticism, he enhances it; the sheer lines "sing" a bit more melodically, and the personalities of the designs are a bit more clearly defined. John could write very well, too, when he wanted to, and he revisits the feel and phraseology of his father's writing now and again, but in general the writing is crisper, more modern, and not as sentimental.

Still, it is a seamless "join" from one man's career to the other, and themes which saw their origin in the father's work in the early years of the century are clearly visible in the son's work decades later.

John Atkin drew the fine little schooner

Florence Oakland,

only 22'5" on deck, for an Ohio man who wanted a traditional, trailerable

daysailer. Nearly 100 sets of plans for the sheet plywood boat have been sent

to builders.

John Atkin drew the fine little schooner

Florence Oakland,

only 22'5" on deck, for an Ohio man who wanted a traditional, trailerable

daysailer. Nearly 100 sets of plans for the sheet plywood boat have been sent

to builders.When custom boatbuilding was the rule, so was custom design. But the advent of fiberglass construction reduced the demand for cruising boat design, and a generalized, if temporary, lack of respect for traditional forms and detailing further served to make yacht design a less dependable way of making a living than it had ever been before. John Atkin never stopped designing until his retirement, but there were lean times as well as prosperous times. Besides a few hundred boat designs, he drew a number of houses for the area surrounding Anchordown, including one that he and his wife Pat built for themselves, next door, and in which they still live. The house designs show the same competence with traditional detail as the boat designs, and the same artistic flair. Atkin also did considerable work as a marine surveyor.

Probably John's most famous design is Maid of Endor, a heavy displacement tabloid cruising sloop, gaff rigged with a bowsprit, a small cabin trunk, and a strong, sweeping sheer. She is rugged in all her details and supremely seaworthy, and loaded with emotion and artistry, but don't ever call her a "character boat" for that is a term John hated. He drew his boats to be the best expressions of their individual concepts that he could create. Their character is just one part of the equation.

As we have noted previously, one must remember that many of the "old- fashioned" boats designed by William were, in fact, perfectly modern when they were drawn. They have simply remained popular for so long that they make us nostalgic when we look at them. On the other hand, to satisfy demand John was working in many of the same design themes and concepts after they had acquired these associations. Therefore the nostalgic references in his designs are more clearly focused, and more carefully calculated, to good effect. His exceptionally deep and broad background enabled him to execute a wide range of older types with complete competence, so that everything works properly, and each design runs true to type throughout. Likewise, he didn't take modern hulls and stick traditional details on them for a cheap effect, as have some recent designers. As John has put it, "I am not keen about the term 'character boat,' the original heading for [this] type of design... because it's been my observation that most any weird creation is likely to be placed in this category. I suspect that people who refer to character boats are often making the distinction between traditional cruising vessels and racing boats.

Shore Liner is an inshore cruising

boat with a lot of room for daysailing and usable sitting headroom below. She'll

float in 1' of water. A flat-bottomed, centerboard boat, she will be comfortable

when grounded out on the mud. She'll never need a cradle, and she will go on and

off a trailer better than just about anything. With her mast in a tabernacle,

it's easy to imagine her finding her way to the furthest inland reaches of

navigable water.

Shore Liner is an inshore cruising

boat with a lot of room for daysailing and usable sitting headroom below. She'll

float in 1' of water. A flat-bottomed, centerboard boat, she will be comfortable

when grounded out on the mud. She'll never need a cradle, and she will go on and

off a trailer better than just about anything. With her mast in a tabernacle,

it's easy to imagine her finding her way to the furthest inland reaches of

navigable water."While we have seen great changes in all forms of endeavor these past 30 years, the transitions throughout the yachting field have been tremendous. Though I don't necessarily like all boats, I have a deep appreciation of virtually all of them; from the latest so-called 'cruiser-racer' (or is it 'racer-cruiser'?)... to the high-speed powerboats of Miami-Nassau fame -- all have admirable ability in fulfilling their intended purpose.

"But there are other purposes, those especially of the people for whom I do design work. My observation is that owners of traditional cruising boats are fundamentally genuine, sincere, quiet gentlemen from all walks of life. Their most predominant characteristic would be individuality, a trait that is apparently fading in this great, corporate land in which we live.

"These people do not base their existence on efficiency or the need to win races. Their aim appears to be incorporating the best that has been proven in the past -- tradition, in a word -- for use in the present. They aim at creating a yacht, power or sail, which combines comfort and the ability to behave, to take care of herself and her crew with a minimum of effort under all -- or very nearly all -- conditions."

John is said to have drawn several well known designs which appeared under other people's names, the Matthews Sea Sailor among them. He seldom employed draftsmen, but one notable exception was the young Jay Benford, who went on to become a famous designer in his own right.

Starting with the Colin Archer-inspired

Eric, both Atkins put considerable emphasis on the evolution of

double-ended offshore cruising boats. Skuld a fine example of

John Atkin's Vixen design,

has straighter sides and narrower beam than the original-for better speed.

Starting with the Colin Archer-inspired

Eric, both Atkins put considerable emphasis on the evolution of

double-ended offshore cruising boats. Skuld a fine example of

John Atkin's Vixen design,

has straighter sides and narrower beam than the original-for better speed.John Atkin also wrote a series of articles for Boat magazine, under the heading "Around the Shop Fire", using the name John Davenport (his middle name), to avoid conflict with Motor Boating, which he regarded as a vital business connection.

John's last design before retirement was a flat bottomed pulling boat for his own use, hearkening back to the many boats of this basic form which he and William drew over the years. She is, as one would expect, the ultimate expression of that form. She is design No. 873, named George, after a little Norfolk terrier who has been John's and Pat's constant companion, and who worked with me some, in preparing for this article. He is visible in the drawings, his head just projecting above the rail.

Those of us who spend much of our lives immersed in the world of wooden boats are apt to ignore the rest of the boating world, and when we are so fortunate as to live in a part of the world which has not been much impacted by the tremendous pressures which are transforming so many waterfronts, as I do, the things that are happening elsewhere can seem somewhat unimportant. Here on the coast of Maine, we are apt to be very satisfied with the direction in which things seem to be moving -- everywhere there are small shops building some of the finest wooden boats ever produced. It is all very comfortable.

When I travel elsewhere, however, I am always disheartened by the harbors I find, full as they are of ugly, boring, inferior, and unsafe boats, and the people who work so hard to acquire and own them, often spending more on boats in a year than I have spent in my lifetime, and seemingly getting so little out of it.

The Atkins are better known for their sailboat

designs, but John on particular was good with rugged cruising powerboats such

as Namaki.

The Atkins are better known for their sailboat

designs, but John on particular was good with rugged cruising powerboats such

as Namaki.It would seem that for many people today boats are just "recreational vehicles," different from motorhomes or dirt bikes only in that they move on the water instead of on the road, and comparable one to another only as lists of equipment, systems, options, and features. In such times, I can think of no finer influence than the melodic, romantic voice of William Atkin, and the artistry and skill of his son, John, as revealed in their writing and in their boat designs. If we can somehow capture the spirit, the love, and the authenticity of their work, and make it continue to speak to us in future years, something precious will be saved, to our lasting benefit and that of the generations to come.

WHEN PREPARING this article I had dinner with John and Pat Atkin at their yacht club on Long Island Sound. It was a stormy evening, with thunderstorms that forced us off the broad lawn and into the building. For a while we stood on the veranda and watched the rain-filled squalls burst out of the yellow western sky and rush off across the water into the gray distance, beyond which lay the lights of Long Island, first visible, and then not. "William Atkin is out there," said John suddenly. "It's where he wanted to be." It was literally true, for William's ashes were scattered in the Sound, according to his wishes, but I also realized that when John looked out at this familiar water he saw and felt a great deal more than the rest of us there that evening -- a world in boats spanning most of the 20th century, which his father and he had savored in every small detail, and furthermore served to create in many unique and graceful ways, the memories of which they worked to illustrate and protect, while helping others to get out of it some of the same joy that they felt.

John passed away in November 1999.

He said in the introduction to a design catalog, "Following in the course so well covered over [the] many years of Billy Atkin has not always been easy. But I appreciate the heritage he left me, as well as the many friends and clients the world over.

"And Shipmate, never forget "the sea remains the same."